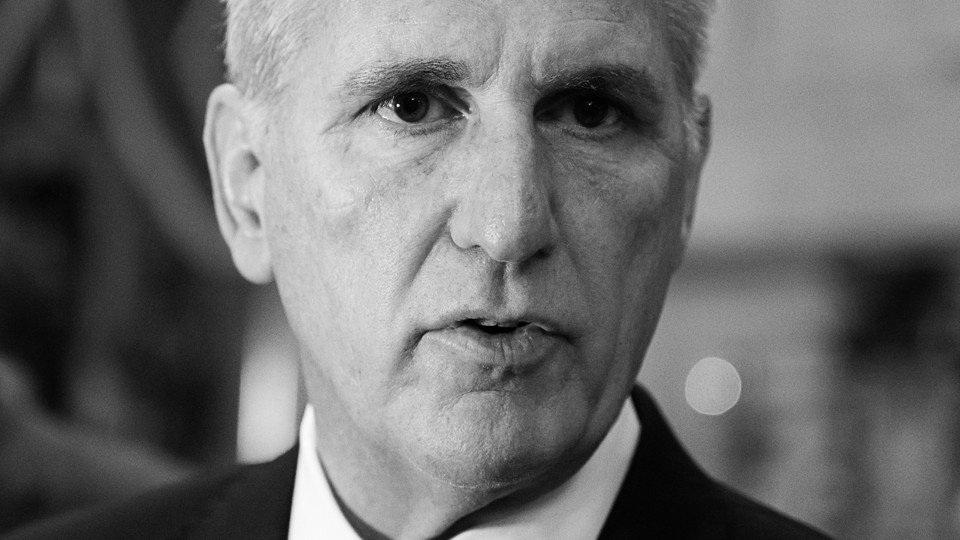

Kevin McCarthy Got What He Deserved

The House speaker surrendered every principle, and in the end, it still wasn’t enough to save him.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

“The office of speaker of the House of the United States House of Representatives is hereby declared vacant.”

With those words, uttered in the well of the House this afternoon, Kevin McCarthy’s reign as speaker came to an inglorious end. McCarthy is the first speaker in history to be removed by his own party; eight Republicans voted to dethrone him, along with all 208 Democrats who were present and voting. McCarthy goes down as having served the shortest speakership since the 1870s.

McCarthy’s defeat was the result of a bitter power struggle within the GOP, and especially due to the efforts of Representative Matt Gaetz, a hard-right rebel, who forced the vote. The House is now without a speaker, and more chaos is sure to follow. The GOP still holds the House majority, but it is a deeply riven and dysfunctional party.

I consider Matt Gaetz to be a maliciously cynical lawmaker, but I can’t say I’m sorry to see McCarthy deposed. After all, he has been a key figure in transforming the GOP into a monstrous political party, one whose contempt for constitutional and democratic norms poses the greatest threat to the republic since the Civil War.

McCarthy was one of 147 Republicans who voted to overturn the 2020 election results—a vote that took place just hours after the January 6 attack on the Capitol. Privately, McCarthy said he would call for Donald Trump’s resignation—“I’ve had it with this guy,” he told other Republican leaders—but once it became clear that the Republican base wouldn’t break with the ex-president, McCarthy did an about-face. He went on bended knee to Mar-a-Lago less than two weeks after Trump incited the insurrection. McCarthy saw rehabilitating Trump as his job, and to some degree he succeeded within the GOP; since that visit, he’s done everything in his power to defend the former president. McCarthy was careful never to get crosswise of Trump, aware of what a dominant figure Trump is within the Republican Party. McCarthy has been so obeisant to Trump—a lawless, cruel, and uniquely destructive figure—that Trump once referred to him as “my Kevin.”

Among Kevin McCarthy’s legacies will be his role in reckless attacks on crucial American institutions, including the Department of Justice. Time and time again, he made unsubstantiated claims about the “weaponization” of the Justice Department. The reason was obvious; McCarthy needed to provide cover for a lawless man. McCarthy surely knew that his incendiary attacks on the Department of Justice were false, but that didn’t matter to “my Kevin.”

McCarthy also forged close ties with Marjorie Taylor Greene, a QAnon conspiracy theorist who aided him in his quest to become speaker. “I will never leave that woman,” McCarthy told a friend, according to The New York Times. “I will always take care of her.” In this case, he was true to his word.

McCarthy also did something unprecedented, campaigning in his role as speaker in a primary against a sitting incumbent in his own party, Liz Cheney, a one-time ally and member of his leadership team. Cheney’s sin? She voted to impeach Trump for inciting the attack on the Capitol; she served as vice chair of the House select committee investigating the January 6 attack; and she continued to call out Trump’s lies about the election being stolen. Cheney acted honorably, placing country above party. She put her political career at risk in order to defend the Constitution. And that was simply too much for “my Kevin.”

Last month, McCarthy announced that he was directing the House to open a formal impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden, after a nine-month investigation led by House Republicans failed to turn up any clear evidence of misconduct by the president. The Republican effort, led by Representative James Comer, has been a clown show. But that didn’t matter to McCarthy; he had a MAGA script to follow, a role to play, a puppet master to dance for. Once again, Kevin McCarthy did the bidding of Trump and the anarchists and political arsonists in his party. In the end, though, no matter how hard he tried, he wasn’t revolutionary enough. When Gaetz went after McCarthy, Trump stayed neutral.

A l’exemple de Saturne, la révolution dévore ses enfants.

What makes McCarthy a particularly pathetic figure is that everyone knows he wasn’t (and isn’t) a MAGA true believer. He had been, up until the Trump era, a fairly mainstream Republican, not terribly ideological, shallow but well-liked among his colleagues. He excelled at fundraising. And he was ambitious. He wanted to be speaker of the House, having tried and failed in 2015. He tried again, earlier this year, and won in a historic five-day, 15-ballot floor fight, after giving major concessions to right-wing holdouts.

“From day one, he knew and everyone knew that he was living on borrowed time,” Representative Gerry Connolly of Virginia told my colleague Russell Berman. McCarthy managed to borrow only 269 days.

During that time, he lived out a cautionary tale of what happens when people with soaring ambitions and no principles gain political power—and what they will do to keep that power.

In Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, Sir Thomas More has an exchange with Richard Rich, an ambitious young man whom More, early in the play, warns against getting into politics. Rich doesn’t possess the moral fortitude to resist the temptations that accompany a political life. It isn’t so much that Rich is bad; it’s that he’s weak.

Rich eventually betrays More, and in one of the play’s most famous lines, More tells Rich, “Why, Richard, it profit a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world ... but for Wales!”

Kevin McCarthy gave up his soul not for Wales but for something worse—Donald Trump. It will be of little comfort to McCarthy to know that he’s hardly the only one to have done so.